Chinese Porcelain in Tanganyika.

Most of the people in Tanganyika and certainly those who live on the coast, know that in days long gone by there was a considerable import trade in Chinese porcelain in East Africa. There are small collections of it in the Dar es Salaam Museum, in Beit Al-Amani, Zanzibar, in the collection of the late Sir Frederick Jackson in the Uganda Museum, as well some in private hands. In the past two years my wife and I have assembled a collection of some four hundred shards from more than thirty ancient sites between the Kenya border and the Rufiji.

From all these sources it is now beginning to be possible to reconstruct a history of this trade for which we have virtually no written evidence but only that of the pots themselves.

We know that in 1417 and 1431 Chinese embassies visited Mogadishu and Malindi : but apart from these occasions, it is concluded by G. F Hourani, whose “Arab Seafarers in the Indian Ocean” everyone interested in East African history ought to read, that trade between East Coast and China was entirely conducted entrepôts, without direct contact. In Duarte Barbosa we read of Indian merchants of Kutch and the Kathiawar coast who brought goods from China to sell to Arabs who came from Siraf in the Persian Gulf and from Oman and who themselves sold to the Arab nahodha or sea-captains who came, as they still do today, in their dhows on the north-east monsoon. In his recent book on his excavation of the Great Mosque of Gedi in Kenya J. S Kirkman describes some of the large quantities of Islamic earthware glazed in yellow with black geometrical designs he has discovered there. The tremendous quantities of this ware, which came from the Middle East, found in tremendous quantities of this ware, which came from the Middle East, found in the rubbish dumps at Gedi and the absence of local pottery other than kitchenware makes it clear that this was the normal ware in luxury use at any rate during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In Tanganyika, where so far no excavations on the scale of Gedi have yet taken place, only two fragments of this ware have been found, one at Tongoni, in Tanga District. In mid-fourteenth century levels this is no longer found at Gedi: it is displaced by a common type of Islamic glazed earthenware with dark and light green, blue, manganese purple and allied glazes. Such glazed pottery has been found at almost every middle Eastern site. Shards of this, but no complete pots, have been found on numerous sites on the Tanganyika coast.

The only complete specimen known to me has been preserved by being cemented onto a tomb at Bweni Dogo, Pangani District. Although there is evidence for the import of Sung celadon wares, it seems that heavy imports of Chinese wares started quite suddenly about the middle of the fourteenth century. We may perhaps connect this with the decline of many Middle Eastern kilns after the collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate as a result of the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century. Failing to obtain good class Middle Eastern earthenware, the Arab importers turned to India and started to buy Chinese wares in the market there. Indeed,apart from finds at Gedi, although some doubtful Sung ware has been found at Tongoni, and a single fragment of Ting ware in Zanzibar, we can say that before the mid-fourteenth century there was probably no steady import of Chinese ware. From then on, there is hardly a single reign of Chinese Emperor not represented in finds of porcelain on the Tanganyika coast up to the mid-nineteenth century.

But, probably because there has been no systematic excavation, examples of the early Ming of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are rare: vast majority of finds belong to the reigns of the Ching Dynasty Emperors K’ang-his (1662 – 1722), Yung Cheng (1723 – 35) and Chien Lung (1736 – 95). Again the mass are of cheap wares intended for common use from provincial kilns of types not to be found among the superior wares in museum collections in Europe and the United States. It is still impossible to state with any precision where a given example was made and to assign it to any precise date. This makes this study particular interest, for it appears to be breaking new ground in the history of oriental ceramics. The vast majority of examples are what are known as blue-and-white: that is, they have a white or bluish-white glaze, with blue underglaze painting. Examples in other colours are very rare. This is often, quite wrongly, known Lamu ware, because it was thought that Lamu was the main centre of import. Turning to the use of porcelain on the coast, by far the most important was certainly domestic: this is certain from large finds in areas such as Chumbageni beach in Tanga and in the rubbish dumps at Gedi and Mboamaji, Kiserawe District, where there is no question of anything else. A true artistic appreciation of porcelain among the Swahili is witnessed by the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century Utenzi Al-Inkishafi, a religious poem which draws a moral from the decline of Pate, written in Lamu dialect:

Wapambaye sini ya kutuewa

na kula kikombe kinakishiwa

Kati watiziye kazi ya kowa,

Katika mapambo yanawiriye.

These lines were freely translated by the late W. Hichens :-

Their banquetings with ware of Ts’in ware spread.

Each goblet with fine graving overlaid;

And, set in the midst, the crystal pitchers made

bright glitter-glow among the napery lain.

But the use best know, though probably least employed, was in the decoration of public and private buildings and especially tombs. This custom may have been introduced from India, where, Duarte Barbosa tells us, the people of Reynel, in the kingdom of Guzerat, had shelves of porcelain round the walls of the principal room of the house. Only two mosques in East African retain their decoration of porcelain plates round the Mihrab or prayer-niche: Chwaka in Zanzibar and Mafui, a remote place in Pangani District. The mosque of Mjimwema once displayed a single plate decorating the ablutions. But formerly, before they were torn out for sale to tourists, there were many more examples. It is sad that so many tombs have been robbed. It is possible that this form had originally an underlying magical purpose, but later the intention seems to have been no more than decorative. This is borne out by the decorative of a small antechamber in the palace of Songo ya Mnara, near Kilwa Kisiwani, with more than 300 plates inset into cavities in the roof; and again by two lines in Al-Inkishafi from which I have already quoted:

Madaka ya nyumba ya zisahani

Sasa walaliye wana wa nyuni.

I again give Hichens’s translation:-

Where once in wall-niches the porcelain stood

Now widling birds nestle the fledging brood.

Far more familiar are the tombs decorated with Chinese porcelain which may be found at almost every historical site. The earliest known of these which has been recently been the subject of a study in Tanganyika Notes and Records by. Mr. Graham Hunter, is a pillar tomb at Kauli, near Bagamoyo : it was decorated with plates of the Yuan Dynasty, (1272 – 1368), of which the two last remaining have been mostly removed to the safe custody of the King George V Memorial Museum. Of the rest the tomb appears to have been robbed. A very similar tomb was excavated recently in Kilepwa in Kenya, and shown to be circa 1350. There are numerous decorated tombs, including pillar tombs, of following centuries but it’s unwise to assume that of all these are ancient. Those at Msanani in Dar es Salaam are probably all of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A pillar tomb at Marungu, Tanga District, bears an inscription dated 1857. At Moa, in the same district, there are tombs with inscriptions giving dates between 1916 and 1937 and decorated with cheap modern European wares. But was the original intention solely decorative? In the Pangani District Book a writer records how at the burial in 1931 of Zumbe Diwani Simba of Mkwaja porcelain plates were ceremoniously broken over his grave. There is a considerable body of evidence of a cult of the dead in which offerings of food and incense are placed in shards of pottery or porcelain at important tombs: at least fifty examples are known to me. Certainly in the Middle Ages there was a widespread belief in the magical properties of porcelain. The Persian philosopher, at-Tusi, who lived from 1207 to 1274, to give one example, in a work written to instruct the Mongol Emperor Hulagu Khan “in the appreciation of ornaments presented to him” informed him that celadon porcelain had definitely magical properties. If food which had been poisoned were placed in a celadon bowl, the glaze would sweat. Powdered celadon was not only excellent as tooth-paste: it was a specific to stop nose-bleeding.

Literary evidence that a similar belief prevailed in East Africa comes from Mozambique, where at unnamed village, the Portuguese pilot Lavanha recorded in 1593: “Coveting a porcelain bottle he saw in the possession of the chief captain, the Chief gave him an ox in exchange, and with great delight seeing it shine and that the glaze would not rub off, he put it to his eyes and to those of his people, and to those parts of the body in which they felt any pain, they persuading themselves it would give them health. And when it was known in the villages that their Chief, who was called Uquine Inhana, had this bottle, they all came to see it, observing the same ceremonies and superstitions.” If evidence is not plentiful, we cannot easily dismiss it. But we cannot surely claim a deliberate magical purpose in more modern times: how then to explain nineteenth century Staffordshire ware chamber-pot which formerly decorated a tomb at Mbweni, Bagamoyo District, or two wine bottles cemented onto a nineteenth century tomb at Bweni Dogo and which are marked Bordeaux Rouge? Rather perhaps it is a relic of former superstition, like our own against passing wine anti-clockwise, of which the reason and origin are forgotten.

References.

G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville Chinese Porcelain in Tanganyika. Tanganyika Notes and Records. The Journal of the Tanganyika Society, 1955, 6:63-66.

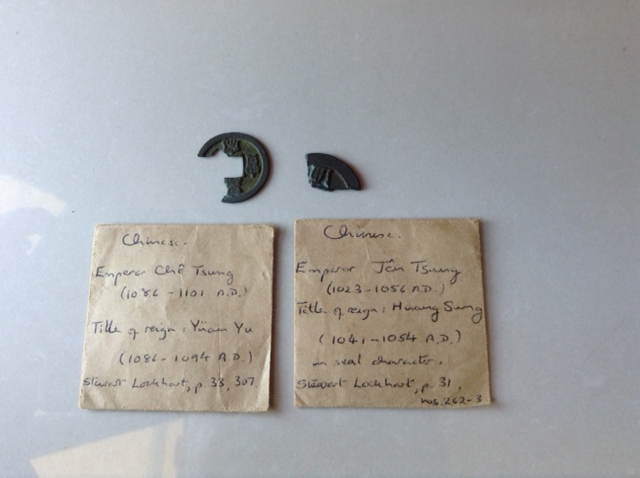

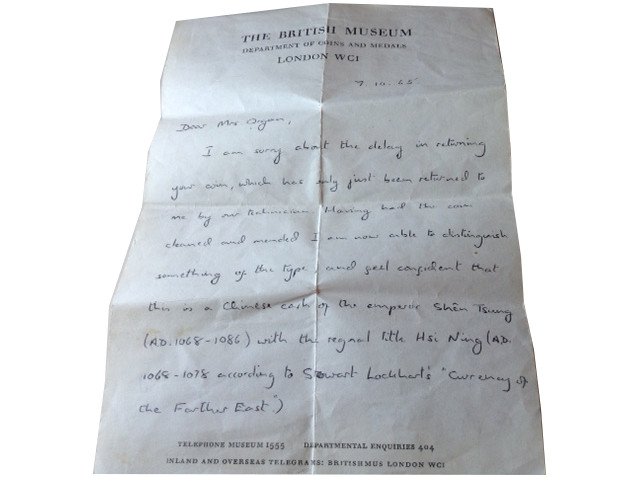

Song dynasty 11th century coins found at Kajengwa Tanzania.The next to it is a British museum letter. A confirmation of early Chinese trade routes to East Africa.

Ming Dynasty chinese verse found in the sea, Probably from the Zheng He period.

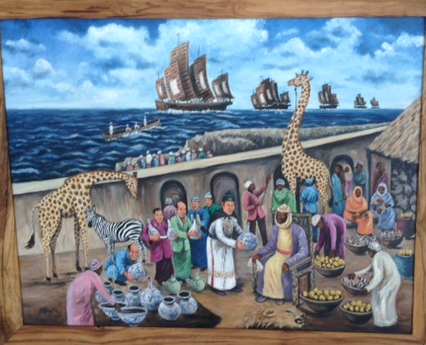

Painting of Zheng He meeting the sultan of Zanzibar.

Pieces of Chards found in Totem Island in Tanzania.